- Home

- Aaron J. French

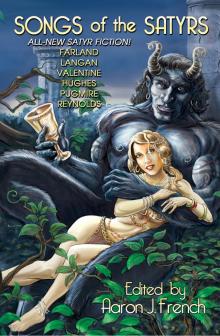

Songs_of_the_Satyrs

Songs_of_the_Satyrs Read online

Songs of the Satyrs

Edited By

Aaron J. French

JournalStone

San Francisco

Copyright © 2015 by Aaron J. French

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, names, incidents, organizations, and dialogue in this novel are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

JournalStone books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting:

JournalStone

www.journalstone.com

The views expressed in this work are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

ISBN: 978-1-942712-24-4 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-942712-25-1 (ebook)

JournalStone 2nd Edition: February 27, 2015

Printed in the United States of America

Cover Art & Design: Gary McCluskey

Edited by: Aaron J. French

Acknowledgements

I want to thank and dedicate this book to Jonathan Rex and Randy Reynolds for all those endless hours of inspiration. The idea for this book germinated with you two; it’s been a long road, but it has finally become real! I would also like to thank Stacey at Angelic Knight Press, Gene O’Neill, Dave Farland, Rhys Hughes, Steve Rasnic Tem, John Everson, Lisa Morton (for the prospectus), and Jessica at Wicked East Press for allowing me to get this project off the ground. And finally, I want to give a personal thank you to Jodi for all her hard work and help with the fantastic editing assistance and copyediting skills. This book wouldn’t be as good as it is without you, and I got to learn a lot, so thank you. To anyone I may have forgotten—dig in your hooves!

Aaron J. French - February 2014

SONNET 129

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action; and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust,

Enjoy'd no sooner but despised straight,

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had

Past reason hated, as a swallow'd bait

On purpose laid to make the taker mad;

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have, extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind, a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

~Shakespeare

SONG OF THE SATYRS

INTRODUCTION

JUDGEMENT

When I am debating whether to purchase an anthology, I give little weight to the theme or shared universe or cover illustration of the book. First, I scan the list of contributors. This weighs heavily in my decision to buy the book or not. Do I trust and respect the various writers who have contributed their time and effort here? Occasionally, there may be one writer in the list of contributors that I admire so much that I will purchase everything with his/her byline. That happens very rarely anymore, because I’m picky and that list of must-have writers is very short; and those writers I really like mostly write longer stuff—novellas and novels. But there is another more important factor weighing in on this buy-or-not decision. It is the name(s) of the editor or editors who have brought this anthology together. Now, I realize many readers often pay scant attention to the editors of anything, unless it is Ellen Datlow, Gardner Dozois, or a name of that stature. But I think when buying an anthology the editor(s) should be of primary significance.

Often, the best editors are just that: they are only editors (e.g. Ellen Datlow). Occasionally a writer I admire will also edit something for some reason (Gardner Dozois). But being a good writer doesn’t necessarily qualify someone to be a good editor. Because being a good editor requires a number of characteristics. Damon Knight was a good writer, but perhaps a better editor. He said that when an editor placed his name on his book he was selling good judgment. Good judgment being the primary characteristic of a great editor. Not automatically buying stuff from your friends or from big names in the field. I know T.E.D. Klein once bounced a Stephen King story for the Twilight Zone Magazine. Damon bounced a number of stories by well-known writers for his ORBIT series, including one by Harlan Ellison—a story that won major awards. Damon said that even had he advance knowledge regarding the reader/critical reception of a story, he wouldn’t change a thing. He didn’t bounce Robert Silverberg’s Nebula-winning short story, “Passengers,” but he required Silverberg to revise it five times. So included with that judgment characteristic is integrity. A really good editor realizes he does himself/the big-name writer no good by publishing something of inferior quality.

No question that Aaron J. French is a fine young writer. Elsewhere I’ve mentioned that one way to judge the health of a genre is to chart the number of emerging good young writers. Right now we have good young writers popping up everywhere in dark fiction. Aaron is one of these writers, on the crest of a breaking new wave.

But the question here is about Aaron J. French’s qualities as an editor. I have been in one anthology he edited, and have read another. I’ve just completed reading Songs of the Satyrs. I don’t know if Aaron automatically buys stuff from his friends, but I suspect he doesn’t. My sampling of Aaron J. French’s editorial efforts indicates to me that he is indeed a very fine editor. He puts together good books, including the one you hold in your hands.

So write down Aaron J. French and place his name with other reminders—on your fridge? Then read everything he writes and buy the anthologies he’s edited because the guy exercises good judgment.

Gene O’Neill

December 2012

Napa Valley, California

TRAGÔIDIA

By John Langan

Dying—he was in sufficient pain to suppose—James Bourne lay in the back of Pascal’s ridiculous half van, his Kangaroo, being driven along the road east from Aigues-Mortes. He had not been to the local hospital often enough to be certain, but he had a strong suspicion Pascal was not headed in its direction. At a guess, they were racing for Provence, for the Camargue proper. That was all right: he could die there as well as anywhere.

***

The worst part was his teeth. As much as anyone could, Bourne had become accustomed to the pain in his shoulders, his hips, his knees. He had taught himself how to move in ways that did not add to his discomfort, and when such discomfort was inevitable, how to move quickly and calmly. He had accepted the shriveling of his desire, and of his cock. To be frank, now that the chemo was done, and his gut no longer felt as if it had been scraped raw, he could tolerate the disintegration of his bones in much better spirits.

His teeth, though: none of the doctors had been able to account for the ache that spread from them through his gums into his face. It prevented him from reading for any length of time. Such pain was not part of the general list of symptoms for metastatic osteosarcoma, so they had blamed it on the chemo—until he finished the treatment and his teeth showed no improvement. For the doctors, it was one more reason for the “atypical” with which they prefixed his diagnosis. Already, he had had the sense that he was moving from a patient to a paper, an interesting case to be presented at their next professional conference. They increased the dosage of his pain medication, an

d the most honest among them estimated that, at the rate the disease was progressing, his teeth wouldn’t be a concern for much longer.

For a short time, the stronger pills had helped to quiet his teeth, had allowed him to concentrate sufficiently to complete his arrangements for traveling to Provence, to finish his final re-reading of Keats’s poems. By the time the flight attendant rolled him off the plane in Marseilles, however, two of the pills were barely adequate to the task. (He had tried three, but they had plunged him into a thick blackness through which the pain had stalked him like a hungry beast.) After he had arrived at the auberge, Pascal had brought him pitchers of sangria, and these, combined with the medication, had allowed him to savor a plate of Pascal’s daube, served with the creamy rice particular to the region. “It’s a miracle,” he’d proclaimed through a mouthful of beef. Pascal had grinned broadly.

It wasn’t, of course. The time for miracles, if ever it had been at hand, was long past. A few days after his arrival, the mix of wine and medicine began to lose its efficacy. He experimented with increasing the amount of sangria he drank, but it had little effect, and anyway, it was a shame to treat the wine as a means to an end, and not an end in and of itself. A brief period of grace had been his: he would try to be satisfied with that.

***

There were five of them. One grabbed his chair from behind and dumped him onto the alley’s cobblestones. The rest set to work with their feet. They were holding long sticks, which they used next. Bourne struggled to shield his head with his arms. The sticks struck his body with dull thuds. He could feel his bones not breaking, but pulping. His attackers were men, far older than the late adolescents he would have assumed would mug an old, crippled professor. One of them was wearing an expensive-looking leather jacket. He wanted to tell them to take his wallet, it was in the knapsack draped across the back of his chair, they were welcome to its meager contents. But one of the sticks had connected with his jaw, and his mouth was numb.

He imagined Pascal had run for the police. He would not have blamed him if he had run away at the sight of five men armed with sticks.

The world withdrew. He wondered if it would return. Perhaps it would be better for everything to end like this, unexpectedly, quickly.

When the world came back, it brought Pascal’s worried face hovering over his. A group of men surrounded him. He did not think they were the same men who had beaten him. At Pascal’s command, they knelt beside him, took hold of his arms and legs, and hoisted him off the ground. An avalanche of pain swept over him. By the time it had passed, he was sprawled in the back of Pascal’s Kangaroo, and they were driving east.

***

A week after Bourne checked-in to the auberge, while he was sitting outside his room by the pool, soaking in the heat of the midday sun, Pascal appeared with a narrow glass bottle half as long again as his forearm and a pair of plain glasses. Hissing when his fingers touched the hot metal, he grabbed one of the chairs scattered on the concrete apron surrounding the pool and dragged it next to Bourne’s wheelchair. He unstoppered the tall bottle, and poured not insignificant portions of its clear contents into the glasses. Bourne accepted the glass he was offered, and returned Pascal’s silent toast.

The eau-de-vie hit him like a blow from a big man. He was sure his expression betrayed him, but Pascal pretended not to notice. Instead, he leaned in close and said, “It’s bad, this sickness.”

“The worst.”

“That’s why you come back here?” The sweep of his hand took in the auberge, the Camargue, Provence.

“Yes.”

“For the Marys?”

“The town?” Bourne said. “Or the church?”

“The church.”

“Why? Have there been reports of miracles performed there?”

Pascal shrugged.

“No,” Bourne said, “I was never that good a Christian. I used to tell my students I found the Greek gods more to my liking. I fancied I could feel them here, next to the Mediterranean where they had flourished for so long. But now . . . ‘Great Pan is dead,’ eh?”

“What does that mean?” Pascal said.

“Nothing. It’s a line from Plutarch, his piece on the failure of oracles. A sailor whose name escapes me heard a voice from shore instructing him to announce the death of Pan to his destination. I think it was his destination. He did so, and there was great lamentation. Report of the incident reached the Roman emperor’s ears, and he took it seriously enough to establish a commission to investigate it.”

“Bullshit,” Pascal said. His cheeks were flushed.

“I—”

“You know who Pan was? Everything.” Another sweep of the hand. “He was one of the old gods—as old as Zeus, maybe older. You think something like that dies?”

“I never knew you were a pagan.”

“Eh.” Pascal looked down. “My father had many books about these things. He told me about them.”

“He was a scholar?”

“Something like that. He is dead many years.”

Another sip of the liquor brought more words to Bourne’s tongue. “I was going to write a paper about Pan—about his presence in the literature of the last couple of centuries. English literature, I mean. That’s why I read Plutarch, for background. I was going to start with Keats, Endymion. There’s a hymn to Pan in it. Keats calls him, ‘Dread opener of the mysterious doors / Leading to universal knowledge.’ It’s the culmination of a series of descriptions of his role in the natural world. I thought I might talk about Forster, too: he has a piece called ‘The Story of a Panic,’ about a group of English tourists who go out for a walk in the Italian countryside and are overcome by a feeling of inexplicable terror. It’s clear they’ve had a brush with the god. Oh, and Lawrence—he refers to Pan in a short novel called St. Mawr. A failed artist described him as ‘the God that is hidden in everything;’ he’s ‘what you see when you see in full.’ ”

“Yes,” Pascal said. “Exactly.”

“Something else I’ll never get around to. I remember thinking I needed to look into Swinburne, to see if I could use him as a bridge between Keats and the Moderns. Ah, well.” He finished the last of his drink. “We have discussed it, so it will not vanish from the world, entirely.”

“Nothing does,” Pascal said. He refilled their glasses.

***

When Pascal turned right off the main road, Bourne thought that it was into a driveway, that he had eschewed the hospital in favor of a familiar clinic or doctor. But they continued driving, deeper into the marshland bordering the road. He had the impression that they were traveling a considerable distance; though it was hard to be sure, because they were moving more slowly, and the road they were following bent from left to right and back again, and every time the wheels jolted in and out of a pothole, a white rush of pain filled him.

The road they were on ended in a small clearing. Pascal parked the Kangaroo at the entrance to it. Before he had finished stepping out of the car, its rear doors swung out. The men who had attacked Bourne were standing there. He was too surprised to speak. They grabbed his useless legs and hauled him forward, catching his arms and lifting him out of the car. Led by Pascal, they carried him to the other side of the clearing, where a gap in the wall of marsh reeds admitted them to a footpath. His ruined bones ground together. Pain as immense as the sunlight washing the sky surrounded him.

Mosquitoes whined about his head. Reeds clattered to either side. The men bore him to the foot of a spring the dimensions of a bathtub. Grunting, they turned around, so that he was facing the direction they had brought him, and lowered Bourne to the ground. His head tilted back, and he could look over the water at the stone from which its source poured. Gray, grainy, the rock had been carved into a face whose features had been weathered to the limit of recognition. What might have been horns, or might have been hair, curled above a wide face whose blank eyes seemed to stare into his above the water that poured from its open mouth.

A hand slid u

nder his head, raised it to Pascal crouched beside him. He was holding a dented tin cup which he raised to Bourne’s lips. The springwater was cold, a benediction. He felt as if he could almost speak.

The hand was yanked away, and his head flopped backwards. Pascal pressed a knife to his throat, and cut it.

***

A couple of days after he’d first arrived at the auberge, once the worst of the jet lag had passed, Bourne rolled himself down the handicapped ramp at the front door to the dirt lot where the guests parked their cars. The lot was empty. He pushed across it to the thick lawn that reached to the marsh. The chair jounced as he wheeled it over the grass to one of the short trees stationed around the space. Once he was under its branches, he halted. His chest was heaving. His arms and shoulders were searing. Sweat weighted his shirt. He sat gazing at the island of green, where Pascal would hold cookouts if the mosquitoes weren’t too bad. Sometimes, he hung lanterns from the trees. Bourne looked at the tall reeds that marked the lawn’s perimeter. How long ago was it he had ventured into them, felt the ground slant steeply down to the water?

A chorus of insects was buzzing its metallic song. In the distance, a white bird lifted into the air. He did not know the name of the insects, or of the bird.

***

Dying was not as hard as he had feared. There was a burning across his throat, and something leaping out of it that must be his blood venting into the air. His body shuddered, too injured already to do any more. Far overhead, the sky was pale blue, depthless as pottery. Closer, water chuckled as the pool was replenished. Then everything went away.

The Dream Beings

The Dream Beings The Demons of King Solomon

The Demons of King Solomon Aberrations of Reality

Aberrations of Reality The Time Eater

The Time Eater Songs_of_the_Satyrs

Songs_of_the_Satyrs